On this day,1 two years ago, I quit alcohol completely. January 15, 2023. It was a Sunday. After twenty-five years of heavy, and more-or-less daily drinking, I drank what turned out to be my last drink ever, and I have not looked back since.

But unlike many other people who’ve kicked the habit, I did not utilize Alcoholics Anonymous (“A.A.”), or any other sort of 12-step program. And the reason I never went to any A.A. meetings—and indeed, the reason why I have never even considered going to one—is very simple:

A.A. DOES NOT LOOK LIKE FUN.

From the outside, A.A. does not look enjoyable, or happy, or exciting, or anything I would call a good time. At best, A.A. looks like a very intense, uncomfortable, and somewhat burdensome form of therapy, and at worst, it looks like a substitute addiction, in the form of a well-intentioned quasi-religion.

But even if all of those preconceptions about A.A. were true—which they probably aren’t—would that really be the best way to decide whether something is a good solution for a drinking problem? How much fun is it? You wouldn’t pick a surgeon or a lawyer based on how much “fun” they were to hang out with; you would pick the most boring, most focused, most serious-looking one you could afford.

So what if your problem is alcohol? If the problem you are trying to solve is your tendency to over-indulge in something harmful that your brain thinks is “fun,” then shouldn’t the solution to that problem necessarily be devoid of fun, and instead, be focused on more serious things? Indeed, isn’t that precisely why AA works? The seriousness, the intensity, the radical honesty—aren’t those the very reasons why A.A. has been so effective over the years at steering people away from alcohol?

Or is it possible that, despite being so effective, A.A. might not be the best way to quit, for you? What are the assumptions that underlie AA, and are those assumptions true as to you, your personality, and your situation? What if the best way to remove alcohol from your life is not by swapping out alcohol for a life of indefinite “recovery?”

Personally, I had—and still have—no interest whatsoever in lugging around “my recovery” for the rest of my life. For all of its faults, that little voice in my head who used to talk me into drinking was a hell of a lot more fun to hang out with than “My Recovery” would be. (“Have you met my recovery? His name is Steve. He’s not great at parties.”).

What if, instead of hanging out with Steve, you could redirect your brain towards a different, healthier, and more productive version of “fun” and allow your brain to overindulge in that instead of alcohol? Furthermore, what if that alternative kind of “fun” was not only wholesome, but also self-sustaining, such that you wouldn’t need to put yourself into an ongoing state of “recovery,” but rather, you could just fix yourself and be done with it; have the same life as before, but with the malignancy removed?

This article is my attempt at answering those questions. However, my aim in writing this is not to persuade you, one way or the other, towards A.A. or away from A.A. Rather, my objective is to help you think for yourself, about yourself, by considering A.A. purely from the standpoint of its suitability to solve a problem, and to evaluate whether it is the best way to solve your particular problem(s) when it comes to alcohol.

Let’s get into it.

A.A. is the O.G.

A.A. has worked for millions of people; this is an indisputable fact. Since 1938, A.A. has been the gold standard, the tried-and-true, the “best practice” when it comes to resolving an alcohol problem. If your parents had a drinking problem, they probably would have gone to A.A. Hell, if your grandparents, or even your great grandparents, had a drinking problem, A.A. would have been the presumptive go-to for them, as well. Simply put: A.A. is the OG.

But perhaps the most interesting thing about A.A.’s longevity is the fact that A.A. hasn’t exactly evolved over time. In the 86 years it has existed, A.A. has changed very little in terms of its foundational documents, including the famous “12 Steps.” In the same way that a shark or a crocodile looks the same way today as it did millions of years ago, A.A. and the 12 steps have remained starkly unmodified despite the changes to the world around them, and to the many people it has served. If there was ever an example of the wisdom of “If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it,” it would be Alcoholics Anonymous.

But even if the 12 steps “ain’t broken,” you have to admit: they do make for a pretty gloomy read, which is ironic, because the 12 steps have a surprisingly colorful history. The 12 steps were famously written by Bill Wilson (aka “Bill W.”), but they were derived from—or at least inspired by—the so-called “Six Tenets”2 of an organization called “The Oxford Group,” a Christian-based temperance society founded around the turn of the century. According to Susan Cheever, author of My Name is Bill: Bill Wilson-His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous, the Oxford Group “aimed itself at the educated and elite, managing to recruit members like Henry Ford, William James, Harry Truman, and Joe DiMaggio.” Bill W. was also a member of the Oxford Group, but at some point, he had a falling out with its leader, Frank Buchman, primarily because Buchman thought that Bill W. was bringing the “wrong kind” of alcoholics to their meetings, which is to say: hopeless, wretched “drunkards,” as opposed the celebrities, business tycoons, and intellectuals that Buchman preferred (many of whom, frankly, didn’t even seem to have drinking problems, but rather, appeared to be jumping on the temperance—slash Eugenics3—bandwagon).

Frank Buchman was a peculiar character in many ways, not the least of which was his strange habit of describing people—or rather, evaluating them—as being either “maximum” or “not maximum.” According to Buchman, a person qualified as “maximum” if they were intelligent, noble, ambitious, and virtuous, whereas a decree of “not maximum” meant that you were somehow lacking in at least one of those categories. For instance, Buchman considered Bill W. to be “not maximum” because of the care and compassion he showed for the wretched, downtrodden, and woefully non-maximum alcoholics he invited into the Oxford Group. In contrast, Buchman went out of his way to bestow his “maximum” credential on none other than Adolph Hitler, whom Buchman believed would “make a great ‘key person’" for the Oxford Group,” and whose existence Buchanan “publicly thanked God for.” In short, Frank Buchman was a Nazi-fan-boy asshole, whereas Bill W. was a very kind and caring guy. As such, Bill W. was wise to cut ties with the Oxford Group and start his own thing.

One thing that truly was “maximum” about Bill W., however, was the manner in which he created the 12 Steps. At the time Bill W. cut ties with The Oxford Group, he was still struggling with alcohol abuse, finding himself in and out of the hospital due to his frequent bouts of binge drinking. And it was fairly soon after one of those hospital stays that Bill W., in something of a fever dream, drafted the 12 steps:

“With a speed that was astonishing, considering my jangled emotions, I completed the first draft. It took perhaps a half an hour. The words kept right on coming. When I reached a stopping point, I numbered the new steps. They added up to twelve.”4

His “jangled” mental state that night was, perhaps, attributable to the care he had received during his most recent hospital stay, where the standard procedure for alcohol poisoning at the time was a combination of barbiturates and a hallucinogen called belladona. Consequently, on the night that Bill W. was drafting the 12 steps, he may or may not have been coming down off some seriously bitchin’ narcotics.

(No judgment here, Bill; Lord knows, I’ve written some important stuff while I was buzzed. Hell, I used to snort Ritalin before I took my law school exams. Same same, bro!).

But perhaps the most impressive thing of all about the 12 steps is the combination of the speed with which Bill W. created them and the complete lack of changes to the 12 steps thereafter. By his own account, Bill W. spent a grand total of thirty minutes writing the 12 steps, after which he (and A.A.) spent the next 86 years not changing a single word of them.

Just to put that into perspective, let’s compare the 12 Steps of A.A. to the Constitution of the United States, which took nearly five years to create (3/25/1785–1/10/1790), including four months of intensive writing, negotiation, re-writing and editing at the tail end, before achieving its final form. Moreover, in the first 86 years after it was put into effect, the Constitution was updated fifteen times (in the form of the First through the Fifteenth Amendments). In stark contrast, Bill W.’s creation of the 12 Steps in a mere half hour—with practically zero updates in the 86 years thereafter—was practically light speed when compared to that of the Constitutional Convention.

As for how Bill W. achieved that double-whammy of speed and immutability, it’s hard to say for sure. I suppose you could chalk it up to “divine intervention,” but alas, the members of the Constitutional Convention were all devout Christians, too, so it seems unlikely that Bill W. would have gotten better customer service from the Man Upstairs than the Founding Fathers did. Plus, even God himself, the Almighty Creator of the Universe, needed a whopping seven days to complete the masterpiece that we call the Earth—a veritable snail’s pace compared to Bill W.’s rate of productivity in creating the 12 steps. Thus, if anything, the Good Lord could have taken his inspiration from Bill W., rather than the other way around.

But the reason why I bring up the history of the 12 steps is to make the point that A.A. seems to have derived a great deal of strength from the fact that it has deliberately not changed itself over the years.

Which brings us to the question: is that a good thing? Is “Ain’t Broken, Don’t Fix It” a good strategy for A.A. to employ when solving the problem of alcoholism? Or should A.A. have been updating itself, in response to the times, throughout those 86 years?

Is “Ain’t Broken” the Same as “Maximum”?

One way to answer this question of whether A.A.’s lack of change has been good for its adherents over the years is to imagine: What if A.A. did update itself? That is, what if A.A. started tweaking, redacting, or just plain overhauling the 12 steps, so as to keep up with changes in society? On the one hand, it would probably appease some of the more easily-offended people out there, but it would also (I think) completely neuter A.A, because over time, constantly nipping and tucking at the 12 steps would take away the ability of its adherents to interpret the 12 steps for themselves. The strength of AA, as far as I can tell, is its adaptability to the individual. Sure, the wording of the 12 steps might be outdated, but that just invites the user to contemplate the steps more deeply, and ultimately, breathe new meaning into the 12 steps for their modern life. If A.A. were to alter or update the 12 steps in the interests of making them more “relevant” or “timely,” it might end up, paradoxically, killing the 12 steps, rather than preserving them for the future.

Here again, let’s compare the 12 Steps to the U.S. Constitution. The reason why the Constitution works so well, and remains a “living” document is because, for the most part, we’ve left it the heck alone. If we started tweaking the Constitution after every election cycle, sure that might clear up a few things, but it would also create a very slippery slope. In short order, the Constitution would become little more than a finger in the wind, gauging the current feelings of the people in charge rather than being a steadfast and timeless beacon for the country to look to and take pride in. In the same way that it is better to interpret the Constitution, rather than amend it, A.A. has left it up to the wisdom of each individual participant to decide what they need from the 12 steps, and what they mean to them.

Thus, one could argue that, “Ain’t Broken Don’t Fix it” is, indeed, a very good philosophy for A.A. and that A.A. is a good solution to the problem of alcoholism.

HOWEVER…

What, exactly, is the “problem” that A.A. is meant to solve? Is it just the removal of alcohol, or is it broader than that? What, exactly, is the end game of A.A.? What is one trying to achieve by going through their program, and what does success look like at the end of the process? Stated differently, what is the thing you are saying “Yes!” to in A.A? What is the reward, the thing you are pursuing?

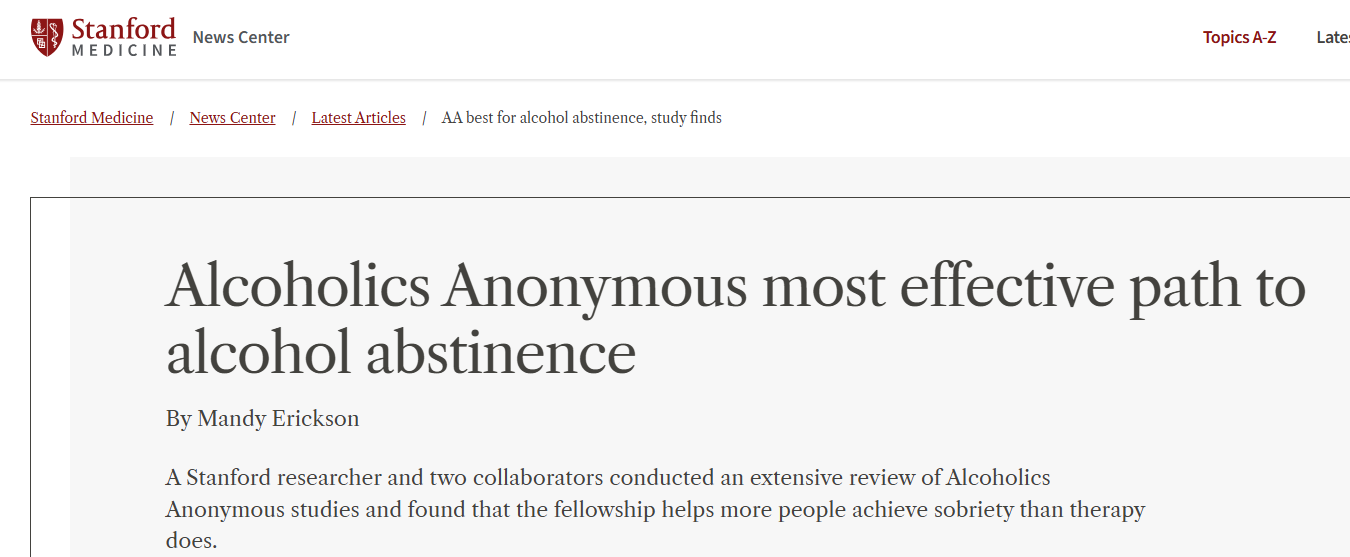

A 2020 study out of Stanford found that A.A. was not only “more effective than psychotherapy at achieving abstinence” but it was “the most effective path to abstinence.” But is mere abstinence the goal? Or is happiness the goal? It could be the case that that Stanford study was right, and that A.A. is, in fact, the best way to achieve abstinence, but is it the best way for you to achieve abstinence and happiness at the same time?

The 12 Steps of A.A, when written out, comprise a total of exactly 200 words, strangely enough, but even stranger is the fact that, of those 200 words, not a single one is the word “happiness,” or even a synonym thereof. This seems more than a little problematic, considering that alcohol use disorders so often stem from, and are perpetuated by, unhappiness. Stranger still is the fact that, of those 200 words, the closest any of them comes to the word “happiness” is the word “sanity” (see Step 25). Meanwhile, there are seven separate instances of capital G “God” and capital H “Him” or “His,” as well as such feel-good topics as your “defects of character,” your “shortcomings” and your “powerless[ness].” Thus, based on the wording of the 12 steps, it would seem that either:

(a) thinking yourself to be insane and/or defective are prerequisites for A.A.; or

(b) at the very least, placing your mental health into the hands of God (or whatever) is a more important part of the process than achieving happiness (or anything like it) is an important part of the results.

Now, obviously, A.A. is not anti-happiness, and the 12 steps are just words, they don’t encapsulate the entire experience of A.A. Furthermore, as for the question of “What does a person pursue in AA?” or “What is the reward you achieve with AA?” the answer might be “salvation,” or “inner peace,” or “I got my life back,” all of which, in the end, might be just as good as happiness. But there again, none of those concepts appear in the 12 steps either. All in all, you have to admit, the 12 steps, as they are written—and have been written, unchanged, for 86 years and counting—do seem to paint a pretty grim picture of “recovery.”

A.A. does work, but it seems to operate on the assumption that the most effective way to remove alcohol from your life is to spend your time, energy, and focus grinding against the friction of your own inadequacies, and that the best way to achieve sobriety is to genuflect your way into it. For those who do achieve happiness through AA—which is a lot of people—it does seem to be a very hard fought win; a happiness forged in a crucible. In fact, many people who succeed with AA seem to take it as a point of pride that it was hard; that they overcame the struggle, embraced the friction and discomfort, and endured the radical honesty of the 12 step process.

But what if all of that struggle and discomfort isn’t actually necessary, for you (even though it might have been necessary and healthy and productive for other people)? The fact that a given person achieves great results from the community, honesty, and intensity of A.A.’s methodology might say more about that particular person’s brain chemistry than it says about the universality of A.A.’s effectiveness.

What if the reason why A.A. works has nothing at all to do with “God,” or “higher powers,” or “powerlessness,” or “defects of character,” or “shortcomings,” or anything else in the 12 steps?

Dopamine is One Hell of a Drug

Speaking of brain chemistry, the 12 Steps of A.A. (as well as A.A.’s “Big Book”) make no mention whatsoever of the concept of neuroscience. This is hardly surprising because, well, A.A. was founded way back in 1938, and (as we’ve already discussed) A.A. does not update its literature. None of A.A.’s foundational materials make any reference to things like dopamine, for example, because alas, when Bill W. was blasting out those 12 steps back in 1938, the discovery of dopamine’s role as a neurotransmitter6 was still 20 years away (1957). Which is ironic, because Bill W.’s dopamine system was probably going absolutely berserk while he was writing the 12 steps.

With all due respect to Bill W., a lot has changed since 1938. Recent scientific data have shown—and most experts in the fields of neuroscience and psychiatry seem to agree—that dopamine is basically the primary propulsion source within the human brain. Simply put, it is why human beings do… EVERYTHING we do! Dopamine has been called the “molecule of more” (which is the title of a fantastic book by Dr. Daniel Lieberman, see below) because it is in charge of motivation, pursuit, seeking, foraging, opportunity, and reward—basically all of the mechanisms that are involved with survival, as well as addiction.

There is also serotonin, which is sort of the yin to dopamine’s yang when it comes to the experience of pleasure. As Dr. Lieberman explains: “As opposed to the pleasure of anticipation via dopamine, [serotonin] gives us pleasure from sensation and emotion.”7 Whereas dopamine is the molecule of more, serotonin is, perhaps, the molecule of “Ahhhhhhhh, that’s nice.” In other words, dopamine and serotonin are directly involved with the human experience of happiness, i.e., the thing that does not appear anywhere in the 12 steps.

Despite their absence from A.A.’s literature, dopamine and serotonin might well be among the primary reasons why A.A. works. The intensity of the environment, the camaraderie of like-minded people sharing radical honesties and exploring their histories to discover the truth—these would all ignite dopaminergic and serotonergic responses. This is, perhaps, why A.A. gets accused of being a cult or a substitute addiction—because for some people, it feels really, really good to go there. And depending on your definition of the words “cult” and “addiction,” A.A. might well be both. But if going to A.A. puts a person into a better headspace than when they were ruining their life with alcohol, isn’t that a good thing? Probably.

Regardless, all of this puts A.A. into a sort of damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t position. If A.A. doesn’t update the 12 Steps or their other literature to incorporate things like modern science, it might be preserving the “timelessness” and adaptability of their methodology, but at the same time, it might be serving fewer people than it otherwise could.

But that, Dear Reader, is A.A.’s problem, not yours. For your purposes, the next question to ask is: What should you do?

The answer, or at least my answer, is: DO WHAT YOU WANT.

“It Works if You Work It.”“It Works if you Want to Work it.”

A.A. has a famous saying: “It works if you work it.” Basically, it means consistency is key and if you stick with the program, it will work. But that statement, I think, is either wrong, or at the very least, incomplete. A.A. (or, for that matter, any other treatment method) only works if you want to keep doing it. And that is only going to happen if you choose a method that engages your brain. As for what “engages your brain” means, you could either think of it as:

(a) What appeals to your spirit and your soul? or

(b) What gets the neurons and neurotransmitters firing inside your brain?

If “working” the 12 steps of A.A. is something that engages your brain, then guess what: A.A. will probably work for you. But if you go to an A.A. meeting and you are not “moved by the spirit” to keep going back—either because of the whole God/higher power thing, or because you just don’t like the group dynamic, or whatever—then it’s probably not for you.

It’s like this: If I was to plop my 9-year-old down in front of a piano and say: “Here you go, son. It works if you work it!” he would look up at me quizzically, stand up, and without saying a word, go back to his room, and return to his baseball cards. Why? Because the baseball cards are a thing he actually wants to do. He wants to “work” the baseball cards; he wants to spend hours cataloging them, alphabetizing them, memorizing the stats on the back, because his brain (and indeed, his spirit and his soul) wants to do that. Inside his little brain, his neurons are firing away whenever he picks up that binder of baseball cards. Meanwhile, he couldn’t give two $hits about the piano. And if he doesn’t want to get better at playing the piano, then it doesn’t really matter—least of all, to him—that he could get better at playing the piano if he just practiced at it. His brain, for better or worse, does not see the piano as an opportunity worth pursuing.

Which brings me back to the title of this article, which is:

The Problem with Alcoholics Anonymous is that I Don’t Want To Do It.

A.A., for better or worse, is just not something that my brain—my formerly cave-dwelling brain that still operates using the same neurotransmitters that it did millions of years ago, and whose signals and instructions we human beings have been trusting for millennia in order to survive—does not see the potential in, and therefore, does not want to pursue A.A. as part of my continued survival.

A.A., to me, is the piano to my son.

Okay, Mister Smarty Pants—What’s Your Solution?

If you think you have a drinking problem, the very first thing you should do is go to an A.A. meeting. Haha! I bet you didn’t see that coming, did you? I know that might sound strange, given what I’ve just said, and given the fact that I was able to quit alcohol without ever going to an A.A. meeting. But do you know what?

I do play the piano.

No, really, I actually play the piano in real life; I took lessons for several years when I was a kid. And it frustrates the $hit out me that neither one of my kids will even try it (aside from just fiddling with the buttons that play the built-in melodies).

You should go try A.A. because screw it, why not? It’s completely free, and there are meetings everywhere, even online, and it presents zero risk to you are anyone else in your life. To the extent that it is a “cult,” it is without a doubt the most benevolent cult in the history of such things. It is not the kind of cult that sneakily, without you knowing, will kidnap you and brainwash you. If it isn’t for you, you don’t go back.

But don’t go to an AA meeting thinking A.A. is going to fix you, or that if it doesn’t fix you, that you are somehow a hopelessly lost cause. A.A. and the 12 steps are a vehicle for introspection. They are on of many avenues by which you can fix you.

I was able to quit drinking without ever going to A.A., but if I was to tell you “Don’t go to A.A.” then that would be me, assuming that what worked for me and my brain is also the best choice for everybody else’s brain, which is an unfounded assumption if ever there was one. If you go to an A.A. meeting and you find it productive or useful or (gasp) maybe even enjoyable, then maybe it’s a thing your brain likes. Maybe A.A. is your baseball cards.

On other other hand, if you decide that A.A. isn’t for you, then you might consider taking the path that I did. As for what that path looked like, well…this article’s getting a little long, and Lord knows, the algorithm hates long articles, so I guess you’ll just have to read my other articles, follow, and subscribe for more, now won’t you! :-)

Happily_AF is a reader-supported publication. All new posts are free for two weeks, after which time they go behind the subscriber paywall. $5/month, or $40 for the year gets you full access to the archive, as well as direct access to me for unlimited Q&A, coaching help, etc. The money is not for me; it is to “encourage” SS algo to transmit this signal to more people. If these articles are helping you with alcohol, pls consider supporting.

As always, thanks for reading, and if you think that you, or someone you know, would benefit from this or any other of my posts, please feel free to like, follow, subscribe, restack, or otherwise share this with them.

Be well.

-DW

Technically it was yesterday. This article took me a little bit longer to edit than I was expecting.

The Six Tenets of The Oxford Group were as follows:

“Men are sinners.”

“Men can be changed.”

“Confession is a prerequisite to change.”

“The changed soul has direct access to God.”

“The age of miracles has returned.”

“Those who have been changed must change others.”

Henry Ford, for example, was a staunch proponent of Eugenics; https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/05/22/trump-criticized-praising-bloodlines-henry-ford-anti-semite/5242361002/

Cheever, Susan; My Name is Bill: Bill Wilson—His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous, p. 153

“2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.”

The actual discovery of dopamine actually happened back in 1910, but at the time, nobody quite knew the full scope of what it did.

Lieberman, Daniel; The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity—and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race, p. 16

To each their own, to be sure, but AA did do it for me - a few funny notes : AA folks describe themselves as “not a glum lot,” seek to live a life that is “happy, joyous, and free” and have “rule 62” not to take themselves seriously.

An interesting note here is I did not bring any religious baggage, so I think that helped me a whole lot.

The women I met in AA are the most badass, tough, wild, fierce group of women I’ve ever met.

Appreciate the thoughtfulness of this piece, thank you.

I started my sobriety in both AA and NA, traditional 12-step programs, though I stopped going after five years of heavy involvement, I do owe a debt of gratitude to them. I have been happily sober and clean for forty years and am an addiction therapist. These programs aren’t for everyone. There can be an aspect of judgement there where people are evaluated by how many meetings they go to and how tightly they adhere to “the program.”

I was taught to “take my own inventory” (e.g. evaluate my own sobriety, not other people’s). Evaluating other people’s sobriety should requested or in the hands of a sponsor or therapist. or something you request, not a knee jerk reaction. It drives people away. I’m gonna do a post on this…